In today’s fast-paced world, multitasking is often seen as a desirable skill, a sign of efficiency and productivity. However, as Dave Crenshaw argues in his book The Myth of Multitasking, what we often call multitasking is actually task-switching (or context-switching as its known in the developer community), rapidly shifting focus from one task to another. This frequent shifting comes at a cost: reduced efficiency, increased errors, and higher stress levels.

In the world of computing, context switching refers to the method by which an operating system saves the state of a process or task so that it can be resumed later, allowing multiple processes to share a single CPU resource. While the mechanisms differ between human cognition and computer processing, the key idea is that frequent switching comes with performance costs in both scenarios.

The Origins of the Multitasking Myth

The term "multitasking" originated in the field of computing during the 1960s, describing a computer's ability to handle multiple processes at once by rapidly switching between them. The first published use of the word "multitask" appeared in a 1965 IBM paper detailing the capabilities of the IBM System/360, a groundbreaking mainframe computer designed to execute multiple programs efficiently. At the time, multitasking referred strictly to a machine's ability to allocate processing power dynamically among various tasks.

As computers became more common in professional and personal environments, the term was increasingly applied to human productivity. By the 1990s, multitasking had become a corporate buzzword, promoted as an essential skill for employees looking to maximize efficiency in fast-paced work environments. Employers and productivity experts encouraged workers to juggle multiple tasks simultaneously, equating human cognition with the rapid task-switching capabilities of computers.

However, neuroscience research has since debunked this notion, revealing that humans, unlike computers, cannot truly process multiple complex tasks at the same time. Unlike a CPU that can divide processing power between independent operations, the human brain must rapidly switch focus between tasks, leading to cognitive overload, decreased efficiency, and increased errors. Despite these findings, the myth of multitasking as a valuable skill persists, deeply ingrained in workplace culture and modern life.

The Science Behind the Multitasking Myth

Scientific research supports the idea that the human brain is not designed for true multitasking. A study published in Science found that when people attempt to juggle two tasks, their brains divide resources between the two hemispheres, assigning each task to a different side. This means that while the brain can handle two simple tasks at once, adding a third creates overload, as there is no additional hemisphere to allocate it to (source).

Other research from Neuroscience News shows that frequent task-switching disrupts brain activity, reducing concentration and increasing stress. This fragmentation of focus results in lower productivity rather than higher efficiency (source).

Additionally, a Stanford University study found that individuals who frequently engage in media multitasking perform worse on cognitive tasks compared to those who focus on one task at a time. Their ability to filter irrelevant information and switch between tasks effectively is significantly impaired, suggesting that chronic multitasking can reduce cognitive control over time (source).

The Computer Analogy: Why Even Machines Struggle with Multitasking

Computers are often used as an analogy for multitasking, but even they don’t truly multitask the way we think. Traditional computer architectures, such as those based on the Von Neumann model, suffer from bottlenecks due to the limited rate at which data moves between the CPU and memory (source).

While modern multi-core processors can handle multiple threads in parallel, their performance still depends on several factors, including memory bandwidth, cache management, and how efficiently tasks are distributed among cores. Additionally, not all tasks can be easily parallelized, some require sequential processing, meaning true multitasking remains elusive even for advanced computing systems. Even within computers, excessive multitasking can lead to slowdowns due to resource contention and inefficiencies in task scheduling.

The Illusion of Multitasking in the Workplace

Despite the evidence against it, multitasking remains a staple in workplace culture. Employees are often expected to juggle emails, meetings, project deadlines, and notifications simultaneously. However, research indicates that this constant switching can reduce productivity by up to 40%, as workers take longer to complete tasks and are more prone to errors. Studies have also shown that multitasking increases stress levels, as the brain struggles to keep up with competing demands. Organizations that prioritize focused work and minimize distractions tend to see higher efficiency and better employee well-being.

Every time someone is interrupted at work, it takes time to refocus and regain momentum. Studies show that after an interruption, it can take anywhere from 15 to 25 minutes to return to the original task with full concentration. These interruptions accumulate throughout the day, drastically reducing efficiency and increasing cognitive fatigue. By minimizing interruptions and reducing task-switching, employees can boost performance, produce higher-quality work, and experience lower stress levels.

Research indicates that this constant switching can reduce productivity by up to 40%

The cost of interruptions is even more significant when an individual is in a flow state, a deeply focused mental state where productivity and creativity peak. If a person is interrupted during flow, it can take even longer to return to that state, sometimes making it impossible to regain the same level of concentration. This is why strategies that protect deep work, such as scheduled focus time and reduced notifications, can lead to significant performance gains. Companies that implement these practices report not only higher output but also greater employee satisfaction and well-being.

The myth of multitasking also extends into meetings and collaboration. For example, if a meeting attendee checks their email, looks at their phone, or works on other tasks while listening, studies have shown that they retain significantly less information and are less likely to contribute effectively. Encouraging single-tasking and undivided attention in meetings leads to better engagement and decision-making.

A Simple Exercise to Prove the Point

To truly understand the inefficiencies of multitasking, try this simple exercise from The Myth of Multitasking by Dave Crenshaw:

Part 1: Single-tasking

Write the sentence:

"Multitasking is a myth."Directly underneath, write the numbers 1 through 20 (since the sentence contains 20 characters, excluding spaces).

Time how long it takes to complete both lines from start to finish.

Part 2 – Task-switching

Write the sentence:

"Multitasking is a myth."

(on the first line).On the second line, directly underneath, alternate between writing a letter from the sentence and a number from 1 to 20:

Start by writing M on the first line, then 1 on the second line, then u on the first line, then 2 on the second line, and so on.Example:

First line: M u l t i s k i n g i s a m y t h

Second line: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20Time yourself again.

You’ll likely find that the second attempt takes significantly longer, and you may even make mistakes. This illustrates the cost of task-switching in a tangible way, each shift in focus requires your brain to reset, slowing down performance and reducing accuracy.

Conclusion: Focus Over Multitasking

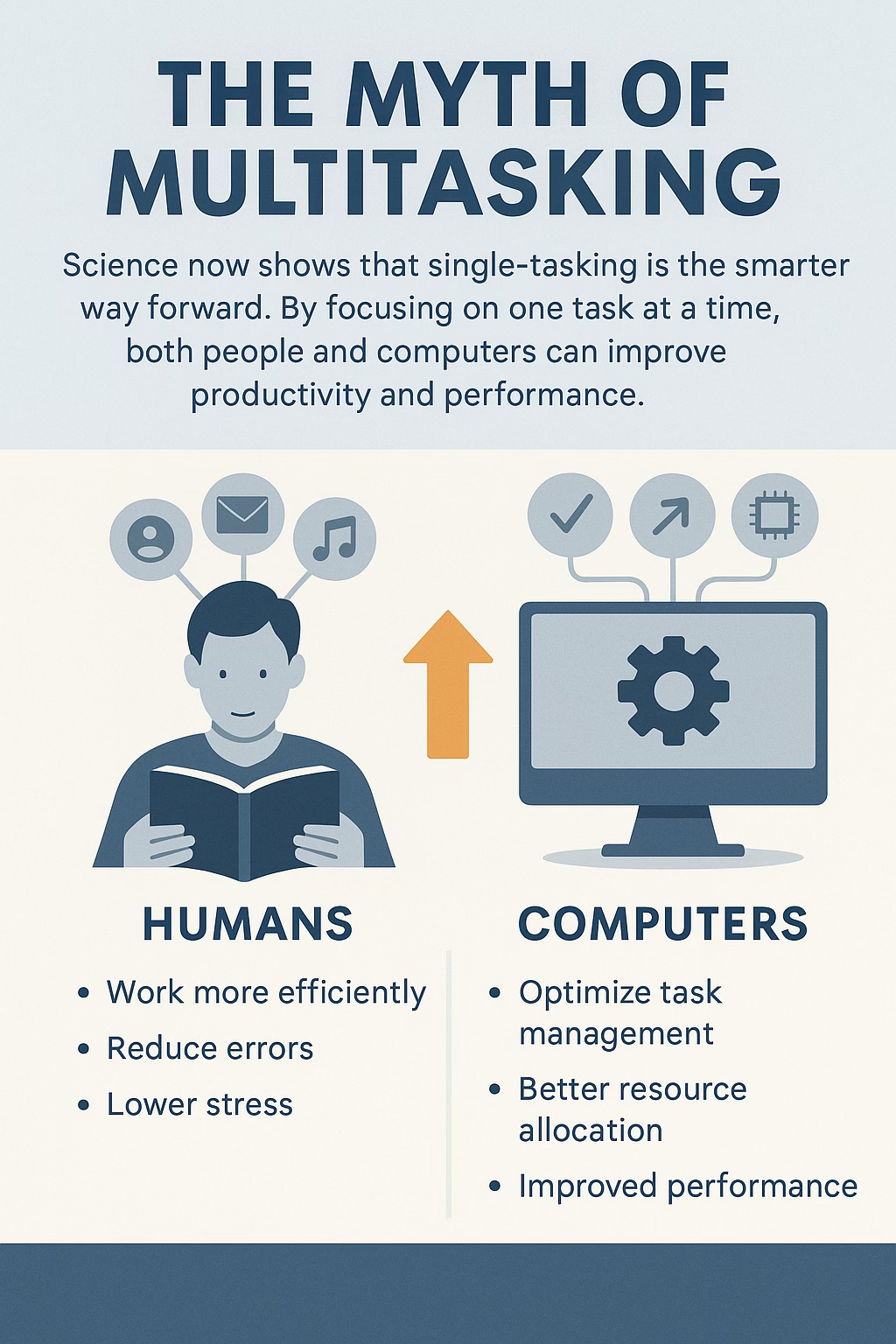

Understanding the limitations of multitasking, both in humans and machines, can help individuals and organizations optimize performance. By focusing on one task at a time, people can work more efficiently, reduce errors, and lower stress levels. Similarly, in computing, optimizing task management and resource allocation leads to better overall performance. Instead of chasing the illusion of multitasking, prioritizing deep focus may be the true key to productivity. The myth of multitasking has persisted for decades, but science now shows that single-tasking is the smarter way forward.

This post hit home. I’ve always worn multitasking like a badge of honor, but your breakdown—and that simple Crenshaw exercise—really made it clear how much productivity I’ve been losing to constant context-switching. I especially appreciated the parallel with computing—how even machines struggle with it. Definitely rethinking how I structure my day now. Thanks, Anders!