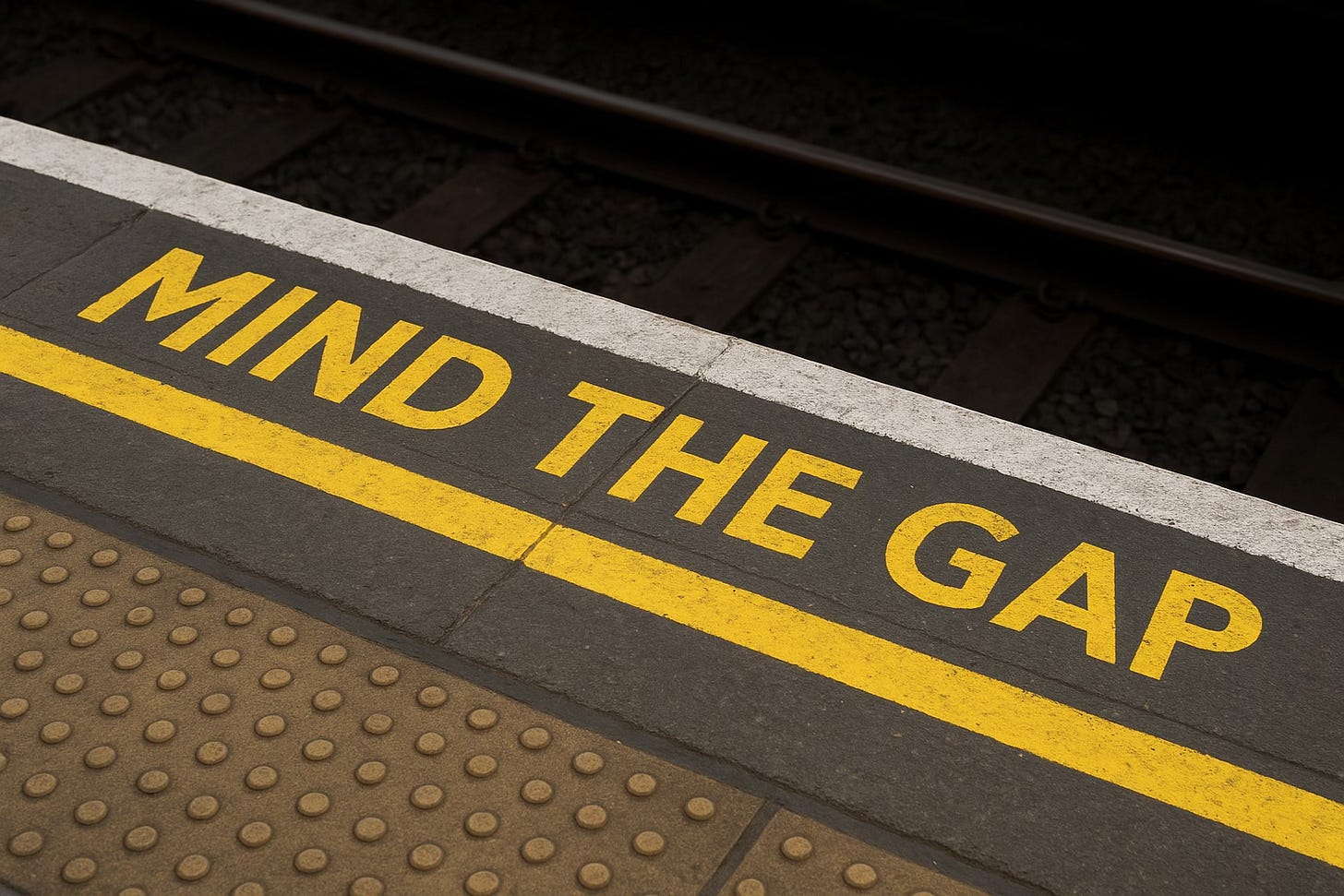

The Hidden Skill Gap

Why top performers from the industrial era struggle in software-defined roles.

For decades, industrial organizations have rewarded reliability, precision, and consistency. The best control engineers, electricians, mechanical engineers, PLC programmers, and OT specialists were the ones who kept processes stable, avoided surprises, and ensured that production never stopped. These people were, and often still are, the heroes of the plant.

However, when organizations move toward software-defined architectures, modern security practices, and data-driven operations, many of these top performers suddenly struggle. Not because they lack intelligence, experience, or commitment, but because industrial excellence and software excellence are governed by fundamentally different rules.

The industrial era rewarded precision, predictability, and stability. The software-defined era still values these outcomes, but the path to achieving them has changed. Industrial systems reach stability by minimizing change. Software systems reach stability by adapting continuously and improving through iteration. This difference creates a natural tension. The habits that drive success in industrial environments do not automatically translate into success in software-centric ones. At the same time, the software-defined landscape still benefits greatly from the industrial mindset. Disciplined processes, clear standards, and repeatable quality remain essential. The principles themselves have not lost their value, what has changed is how they must be applied.

This is the hidden skill gap. It affects not only engineers and architects, but also the organization as a whole, especially management. Leaders decide who gets promoted, who is assigned new responsibilities, and which projects receive funding. In many organizations, there is an implicit assumption that strong performers from the industrial world will naturally succeed in software-defined roles. It feels logical and safe to promote the people who have delivered reliably for years and who know the environment better than anyone else. But unfortunately, this assumption often leads to slow failures that take years to surface. Fragile architectures, weak cybersecurity foundations, vendor lock-in, unrealistic project plans, and expensive rewrites emerge gradually. These outcomes are rarely the result of negligence or poor intent, they occur because the organization misjudged what the new roles actually require.

Different Rules, Same Goals

Industrial automation is built around availability, determinism, long equipment lifecycles, and strict change control. Success comes from reducing variability and ensuring that the same action produces the same result every time. In this environment, experience and adherence to proven processes are rightly rewarded. Software engineering and modern OT security pursue similar goals, but they reach them through different means. They rely on abstraction, iteration, continuous learning, and the ability to respond to evolving requirements and threats. New languages, architectural patterns, and threat models appear constantly. Remaining effective requires ongoing engagement with change. A control engineer who limits change is doing exactly what their environment demands. A software architect who limits change falls behind. Both approaches are rational within their own domains, but they do not translate automatically across them. The challenge is not to replace one mindset with the other, but to combine their strengths without assuming that mastery in one domain implies mastery in the other.

Management’s Blind Spot

Many leaders in industrial organizations built their careers on operational stability rather than software complexity. As a result, they often have limited exposure to what it takes to design resilient software architectures, implement secure networked systems, or manage OT environments in a constantly evolving threat landscape.

Management or managers does not need to be hands-on experts, but they must understand the constraints, risks, and skill requirements well enough to make informed decisions. When the skill gap is underestimated, predictable patterns emerge:

Senior PLC programmers and control engineers are promoted into software architecture or cybersecurity roles without sufficient grounding in modern software principles.

Modernization initiatives are expected to move quickly, even though operational teams remain focused on minimizing change.

Budgets are approved for vendor solutions without a clear understanding of long-term trade-offs or internal capabilities.

The consequences are subtle at first, but they accumulate over time. Systems become brittle, vulnerabilities are overlooked, dependency on vendors increases, and projects stall or quietly underdeliver. Management’s trust in past performance becomes the very blind spot that allows these issues to persist.

Why Mastery Takes Time

Proficiency in software-defined systems cannot be achieved overnight. Network engineers, software developers, architects, and cybersecurity professionals acquire expertise through years of hands-on work, mentorship, experimentation, and reflection. They learn to navigate complex dependencies, identify subtle failure modes, and anticipate emerging threats. Mastery comes from exposure to real-world scenarios where the consequences of decisions are tangible and often irreversible.

For industrial professionals transitioning into software-defined roles, the challenge is not a lack of intelligence or diligence. It is the need to develop a fundamentally different skill set. Control engineers and OT specialists are accustomed to systems that prioritize stability by minimizing change. In software-defined systems, success depends on controlled experimentation, rapid iteration, and the ability to adapt processes and architectures in real time. This requires comfort with ambiguity, resilience to failure, and a mindset oriented toward continuous improvement.

Organizations often underestimate the time and support required for this transition. Expecting a title change, a short training course, or occasional workshops to replace years of deliberate practice is unrealistic. Structured guidance, mentorship, access to sandbox environments, and opportunities to experiment without catastrophic consequences are critical. Patience and deliberate skill-building are investments, not delays, and they ultimately reduce the cost of errors and accelerate long-term performance.

The Consequences of Ignoring the Gap

When the hidden skill gap is ignored, projects may appear successful on paper but often fail in reality. Architectures look clean in planning stages but collapse under changing requirements. Security controls meet compliance checklists but fail against real-world threats. Internal teams lack the ability to critically evaluate vendor solutions, leading to long-term lock-in. Over time, capable individuals are placed under impossible expectations. Frustration grows, burnout increases, and organizations struggle to understand why well-intentioned modernization efforts never fully deliver. These failures are not personal shortcomings. They are systemic mismatches between historical expertise and modern demands.

Bridging the Gap

Acknowledging the hidden skill gap is the first step toward building resilient software-defined operations. Organizations that successfully navigate this transition adopt deliberate strategies to combine industrial discipline with software agility.

1. Build hybrid teams.

Pair OT experts with software engineers, security specialists, and architects. Encourage knowledge exchange through collaborative problem solving. Cross-functional teams allow industrial expertise to inform software decisions while software practices shape operational thinking.

2. Define roles and responsibilities clearly.

Avoid the assumption that previous success guarantees readiness for new roles. Architects should focus on design, developers on implementation, and operational experts on managing physical systems. Hybrid responsibilities should be explicit and supported with training and mentoring.

3. Invest in structured learning paths.

Develop step-by-step learning programs that combine theory, hands-on exercises, and exposure to real-world challenges. Provide mentorship from experienced software or cybersecurity professionals who can guide industrial experts through the nuances of abstraction, iteration, and adaptive practices.

4. Create safe experimentation environments.

Sandboxes and testbeds allow teams to learn, iterate, and fail safely. These environments replicate production conditions without risking operational stability, giving individuals the freedom to explore new technologies, architectures, and threat models.

5. Encourage continuous learning and curiosity.

Reward adaptability, proactive skill development, and experimentation alongside operational excellence. Recognize that curiosity and the willingness to question assumptions are as critical as technical competence.

6. Align leadership expectations with learning curves.

Management should understand that skill development in software-defined systems takes time. Project timelines, budget allocations, and promotion decisions must reflect the reality of learning curves. Unrealistic expectations create pressure, frustration, and burnout.

7. Document and iterate processes.

Even in software-defined environments, disciplined processes remain valuable. Encourage teams to document practices, lessons learned, and architectural patterns. Iterating on these processes allows organizations to scale knowledge and embed both industrial rigor and software agility into the culture.

By blending the structured discipline of industrial systems with the adaptive, iterative practices of software-defined operations, organizations can close the hidden skill gap. The result is teams that deliver innovation and operational reliability simultaneously, architectures that remain resilient under change, and cybersecurity measures that withstand evolving threats.

Conclusion

The hidden skill gap is not a failure of individuals. It is an organizational blind spot shaped by decades of success in a different era. Industrial excellence and software-defined excellence aim for the same outcomes: stability, reliability, and safety. What differs is how those outcomes are achieved.

When organizations assume that past mastery automatically translates into new domains, they create fragile systems and frustrated teams. When they recognize that software-defined roles require different skills, longer learning curves, and new ways of thinking, they gain clarity. Promotions become intentional. Architectures become more resilient. Security becomes more than a checkbox exercise.

Closing the hidden skill gap does not mean abandoning industrial values. It means evolving how those values are applied. Organizations that do this deliberately build teams capable of sustaining both operational excellence and continuous change. In a software-defined world, that balance is no longer optional, it is the difference between long-term resilience and slow, but often invisible, failure. Time is required for mastery, and curiosity, adaptability, and continuous learning should be rewarded alongside proven industrial experience. By blending the rigor of the industrial era with the flexibility of software-defined thinking, organizations can achieve reliability, predictability, and stability in the modern OT environment.

“Great leaders do not assume past success guarantees future results, they cultivate the skills, curiosity, and courage their teams need to thrive in a changing world.”

Related Articles

Explore more of my writing on related topics below.

The Real Reason Your Process Isn’t Working

Before we get started, I want to clarify a common source of confusion: Many people mistake processes for policies, but understanding the difference is (in my opinion) critical. A policy sets the principle or rule: it tells you what should be done and

Why Cybersecurity Belongs in the Boardroom

When we talk about cybersecurity, many business leaders still think of it as a purely technical challenge: firewalls, passwords, and antivirus software, just to name a few. In reality, it is also a business issue. At its core, cybersecurity is about managing risk, controlling costs, building trust, and ensuring resilience. Trust, continuity, and competi…

The Living Reference Architecture: Adapting to Stay Ahead of the Curve

Exploring Reference and Solution Architecture: A 3-Part Series